OKT hosts the last session of its 2015 Food Justice series Saturday, 10 a.m. to noon at Garfield Park Lodge, 334 Burton St. SE. We will discuss how we each can work for food justice here in Grand Rapids. Stop on by!

Reposted from Civil Eats By Kristin Wartman on September 3, 2015

While the Black Lives Matters movement works to stop police violence, another less-visible form of structural violence is taking place all across America.

In the wake of the unrest in Ferguson, Missouri, after the death of Michael Brown, the Baltimore uprising after the death of Freddie Gray, and the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement, much has been written about the nature of poverty and violence in American cities. But one aspect that is chronically underreported is the lack of access to healthy foods in many of those same communities. Indeed, the reliance on a highly processed food supply is causing disease, suffering, and eventual death, especially to those in the poorest of neighborhoods.

A report released this June by the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future found that one in four Baltimore residents lives in an under-resourced area or “food desert” (a term that some food activists reject). This is not unusual or unique to Baltimore, but is the standard in urban centers throughout the country. Only eight percent of Black Americans live in a community with one or more grocery stores, compared to 31 percent of white Americans.

And while food is by no means at the center of the Black Lives Matter movement, it could emerge as an important corollary issue in the months and years to come.

“The fact is, I can’t get an organic apple for 10 miles,” said Ron Finley, known as the “gangsta gardener,” who lives in South Central, Los Angeles. “Why is it like that? Why don’t certain companies do business in these so-called communities? ‘Oh there’s no money,’ they say—there’s money. If there’s no money than why are there drugstores here? Why are the dialysis centers here? Why are there fast food restaurants? What there is, is disregard for these places.”

The disregard that Finley speaks of has vast implications for the health of people living in areas with little access to healthy, whole foods. Meaning that a significant threat to Black lives comes from our food supply itself—from the glut of fast food and other highly processed food options and the virtually unregulated chemical additives that lace these foods.

The rates of diet-related disease break down dramatically along racial lines. African Americans get sick at younger ages, have more severe illnesses, and die sooner than white Americans. The American Journal of Public Health found that Blacks scored almost 50 percent higher than whites on a measurement called Allostatic Load, the 10 biomarkers of aging and stress. While there are clearly multiple factors at work, diet plays a significant role in these findings.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the rate of obesity for African Americans is 51 percent higher than for white Americans and one in two African Americans born in the year 2000 is expected to develop type 2 diabetes. Compared with white adults, the risk of diabetes is 77 percent higher among blacks. The rates of death from heart disease and stroke are almost twice as high among African Americans.

Just as our economy has become starkly stratified with wealth concentrated at the top, it is increasing clear that we live in a two-tiered food system in which the wealthy tend to eat well and are rewarded with better health, while the poor tend to eat low-quality diets, causing their health to suffer. A report released last year by the Harvard School of Public Health found that while diet quality improved among people of high socioeconomic status, it deteriorated among those at the other end of the spectrum, and the gap doubled between 2000 and 2010. African Americans experience the highest rate of poverty in the U.S.—25.8 percent, compared to 11.6 percent of whites. And 45.8 percent of young Black children live in poverty compared with 14.5 percent of white children.

Dr. Marvin L. “Doc” Cheatham, Sr., President of the Matthew A. Henson Neighborhood Association in Baltimore said he sees this in his community. “Stop allowing there to be two Baltimores,” he wrote in an email. “Have the Health Department and our elected officials place more funding and more emphasis on poorer, neglected, communities….”

The solution to food inequality has traditionally been framed as a problem of access and education: Bring healthy foods into under-served communities and educate those living there on healthy eating, the argument goes. But just as getting oneself out of poverty is far more complicated than working hard and getting an education, maintaining a healthy body by “choosing” to eat well is far more complex than making simple decisions about what to eat in our current food landscape.

In both cases, the ideology of “personal responsibility” is invoked, which fails to address deeper, structural issues like the myriad causes and effects of poverty. As author and University of California Santa Cruz professor Julie Guthman puts it, “Built environments reflect social relations and political dynamics…more than it creates them.”

When we frame the problem in terms of simplistic solutions, like “better access to fruits and vegetables” or “education about healthy eating” the underlying structures remain and the food, agricultural, and chemical industries are not impacted at all. As Ta-Nehisi Coates’ writes in his new book Between The World And Me, “The purpose of the language of … ‘personal responsibility’ is broad exoneration.”

I asked Karen Washington, a food activist and farmer at Rise & Root Farm in the Bronx, what she thought about creating better access in “food deserts.” “Bringing a grocery store into food insecure neighborhoods is not the answer,” she wrote in a recent email. “What needs to be addressed is the cause of food insecurity; the reason for hunger and poverty. Do you really think that bringing a supermarket into an impoverished neighborhood, where people have no jobs and no hope is the solution? Heck no!”

According to the latest U.S. Department of Labor report, the rate of Black unemployment is more than double the rate of white unemployment—9.1 and 4.2 percent, respectively. Workers wages have been stagnant across the board for the past decade but for black workers, wages have fallen by twice as much as they have for whites in the past five years.

Washington says that the bottom line is that people need jobs. “No one talks about job creation, business enterprises, or entrepreneurships in low-income communities,” she said. “We have to start owning our own businesses, like farmers’ markets, food hubs, and food cooperatives. When you own something it gives you power.”

Finley wants to see more people growing food for themselves and their neighbors. He says the focus is too often merely about bringing food into communities. “People don’t have any skin in the game. I want people to have some kind of hand in their food. I don’t care how rich you are, if you don’t have a hand in your food, you’re enslaved,” he said.

Of course, it’s critical to point out that for many people of color, the danger of immediate bodily harm is far more pressing than concerns about long-term health effects. As Washington sees it, it doesn’t make sense to apply the Black Lives Matter Movement directly to food. “The only correlation is that people are tired of the injustices that plague their communities each and every day and are starting to take action and matters into their own hands,” she said.

But it’s also clear that the Black Lives Matter movement is expanding. “We are broadening the conversation around state violence to include all of the ways in which Black people are intentionally left powerless at the hands of the state,” reads the group’s website.

It’s crucial to bring issues around food and health into dialogue with discussions of structural racism, poverty, and violence in this country. “What are they feeding us if we have more diseases than we’ve ever had before in certain communities?” asks Finley. “You have asthma, hypertension, diabetes, obesity—and all of this stuff is food-related.”

Finley says this makes for an obvious connection to the Black Lives Matter movement. “We’re under siege and a lot of these communities are being occupied and terrorized—by food companies,” he said.

Have you ever wanted to grow a food garden but didn’t know where to start?

Have you ever wanted to grow a food garden but didn’t know where to start?

One of the most infuriating aspects of the Flint water crisis is that residents are not only still being charged for their poisoned water, but they’re being charged higher rates than almost anywhere in the country.

One of the most infuriating aspects of the Flint water crisis is that residents are not only still being charged for their poisoned water, but they’re being charged higher rates than almost anywhere in the country.

Each Cook, Eat and Talk event demonstrates how to prepare an easy, affordable, nutritious, in-season menu option. While participants enjoy tasty samples, the cooking coaches take them through a four-page lesson journal, in Spanish and English, that inspires dialogue on making healthier food choices and introduces food justice principles.

Each Cook, Eat and Talk event demonstrates how to prepare an easy, affordable, nutritious, in-season menu option. While participants enjoy tasty samples, the cooking coaches take them through a four-page lesson journal, in Spanish and English, that inspires dialogue on making healthier food choices and introduces food justice principles. All of our cooking coaches are food gardeners, as well. Toni grew up gardening and grows her own food as part of a healthy eating plan that helps her deal with MS. She spends a lot of time cooking healthy alternatives for her family, neighbors and congregation. Marcia and Isis are both dedicated vegans and bring a vegetarian flair to the dishes they share. Alynn is a print-maker by trade. Much of the work she creates at her

All of our cooking coaches are food gardeners, as well. Toni grew up gardening and grows her own food as part of a healthy eating plan that helps her deal with MS. She spends a lot of time cooking healthy alternatives for her family, neighbors and congregation. Marcia and Isis are both dedicated vegans and bring a vegetarian flair to the dishes they share. Alynn is a print-maker by trade. Much of the work she creates at her

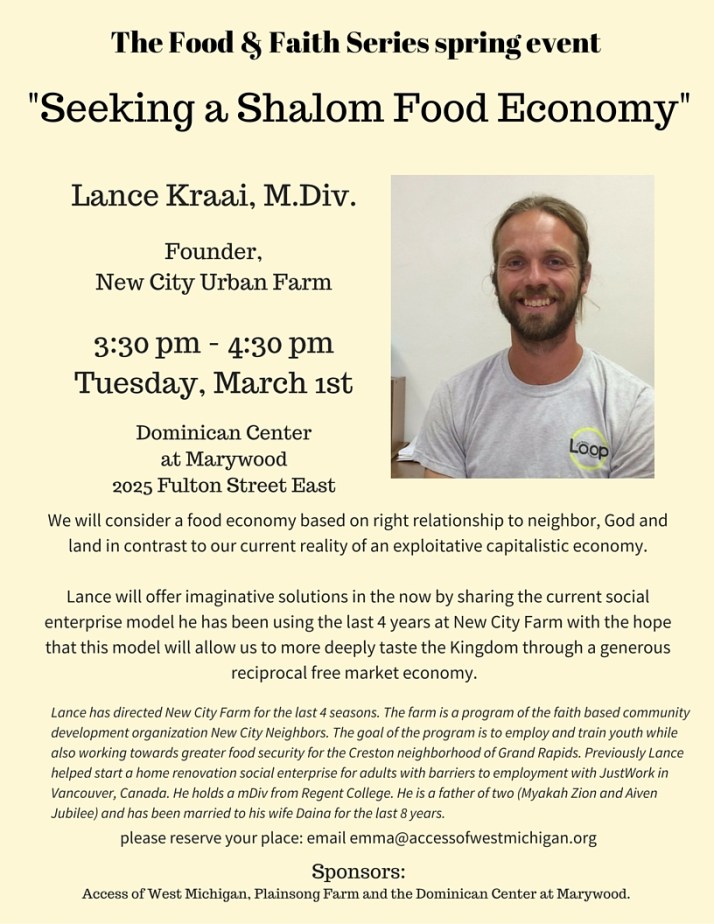

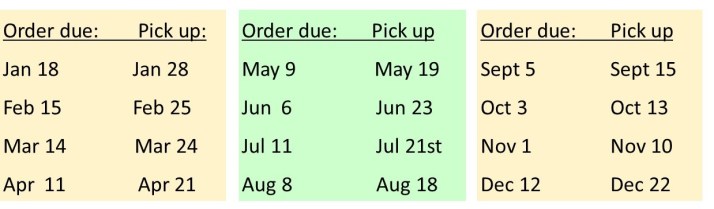

Place your bulk

Place your bulk  Please join OKT for week 2 of its free, four-session class series that explores what is food justice is, why we need it and what we can do in Grand Rapids to make it happen. The class, “The Food Justice Movement: Moving Forward,” will meet 10 a.m. to 12 p.m. Saturdays Nov. 21, Dec. 12 and Dec. 19 at Garfield Park Lodge, 334 Burton St. SE 49507.

Please join OKT for week 2 of its free, four-session class series that explores what is food justice is, why we need it and what we can do in Grand Rapids to make it happen. The class, “The Food Justice Movement: Moving Forward,” will meet 10 a.m. to 12 p.m. Saturdays Nov. 21, Dec. 12 and Dec. 19 at Garfield Park Lodge, 334 Burton St. SE 49507. The Southeast Area Farmers’ Market is hosting its first indoor market 6 to 8 p.m. Thursday Nov. 19 at

The Southeast Area Farmers’ Market is hosting its first indoor market 6 to 8 p.m. Thursday Nov. 19 at